Yayoi Period

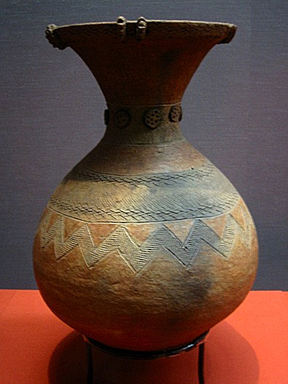

A Yayoi Jar

弥生時代 - The Yayoi Period

300 BC - 300 AD

This period of Japanese history is named after a district in Tokyo where, in 1884, a reddish-brown, plain type of pottery was discovered. The type of pottery was clearly distinct from the Jomon period. It is a bit ironic that the pottery was very "plain" whereas the period was anything but.

The Yayoi period saw many drastic changes in the land of Japan. The people moved from hunting and gathering to agriculture; from nomadic living to settlements; from stone tools to metal tools; and from 'barbarous' society to a hierarchical society. Japan also experienced a civil war during this period. All of these changes helped pave the way to the future unification of Japan. The Yayoi period also saw Japan's first recorded history, albeit written by the Chinese.

One of the most important aspects of the Yayoi period was the sort of "invasion" that occurred from mainland Asia. Whereas it is most likely that large groups of people immigrated from mainland Asia, some historians argue that it is merely the culture that immigrated. The Yayoi people were different from the Jomon people both in culture and in appearance. They generally came around 300 BC, were taller, lighter, and had narrower faces, used bronze and iron, and ate a much more rice-rich diet.

Why did they come and in what numbers did they come? Did immigrants even come at all? These questions are not known for sure. However, the (most likely) immigrants made countless changes to Japan that are still felt today. The Yayoi people most likely came into Japan through Kyushu (Kyuushyuu 九州) and spread northeast through to mid-Honshu (Honshyuu 本州) by the end of the first century AD. They were unable to push into northern Honshu. Northern Honshu remained as a distinct culture until the 8th century. There is still, today, a bit of a culture gap between the north and south of Japan.

Rice had been introduced to Japan thousands of years earlier, but the new-comers produced and consumed it in much greater abundance than the Jomon people. They developed rice paddies which were predominantly located in the south and western areas of Japan. With this increased agriculture socially stratified societies were bound to be created, and, indeed, localized chiefs arose. With chiefs beginning to dominate permanent settlements (kuni), eventually armies, warriors, and further hierarchy began to arise. Some kunis came to consist of some hundred families. When those of lower rank came across those of higher rank on the road, it was expected that they would step aside and bow as the higher ranked individuals passed. This tradition continued into the 19th century. With hierarchy came slavery.

Increased rice production also meant the need to store grains. This simple need, along with the introduction of iron and bronze production, led to homes raised off the ground. However, the majority of homes were still circular dig-outs in the ground. The raised homes helped prevent spoilage from dampness and rodents. The increase in rice consumption also explains why the Yayoi were generally taller than the Jomon people.

The Yayoi people were also known for burying their dead in graves. Before burying them, the deceased would be placed in large ceramic urns or stone coffins. These graves are surrounded by raised mounds or stone circles and are found in clusters which suggests that the deceased were buried in cemeteries of sorts, as opposed to simply being buried in random locations.

300 BC - 300 AD

This period of Japanese history is named after a district in Tokyo where, in 1884, a reddish-brown, plain type of pottery was discovered. The type of pottery was clearly distinct from the Jomon period. It is a bit ironic that the pottery was very "plain" whereas the period was anything but.

The Yayoi period saw many drastic changes in the land of Japan. The people moved from hunting and gathering to agriculture; from nomadic living to settlements; from stone tools to metal tools; and from 'barbarous' society to a hierarchical society. Japan also experienced a civil war during this period. All of these changes helped pave the way to the future unification of Japan. The Yayoi period also saw Japan's first recorded history, albeit written by the Chinese.

One of the most important aspects of the Yayoi period was the sort of "invasion" that occurred from mainland Asia. Whereas it is most likely that large groups of people immigrated from mainland Asia, some historians argue that it is merely the culture that immigrated. The Yayoi people were different from the Jomon people both in culture and in appearance. They generally came around 300 BC, were taller, lighter, and had narrower faces, used bronze and iron, and ate a much more rice-rich diet.

Why did they come and in what numbers did they come? Did immigrants even come at all? These questions are not known for sure. However, the (most likely) immigrants made countless changes to Japan that are still felt today. The Yayoi people most likely came into Japan through Kyushu (Kyuushyuu 九州) and spread northeast through to mid-Honshu (Honshyuu 本州) by the end of the first century AD. They were unable to push into northern Honshu. Northern Honshu remained as a distinct culture until the 8th century. There is still, today, a bit of a culture gap between the north and south of Japan.

Rice had been introduced to Japan thousands of years earlier, but the new-comers produced and consumed it in much greater abundance than the Jomon people. They developed rice paddies which were predominantly located in the south and western areas of Japan. With this increased agriculture socially stratified societies were bound to be created, and, indeed, localized chiefs arose. With chiefs beginning to dominate permanent settlements (kuni), eventually armies, warriors, and further hierarchy began to arise. Some kunis came to consist of some hundred families. When those of lower rank came across those of higher rank on the road, it was expected that they would step aside and bow as the higher ranked individuals passed. This tradition continued into the 19th century. With hierarchy came slavery.

Increased rice production also meant the need to store grains. This simple need, along with the introduction of iron and bronze production, led to homes raised off the ground. However, the majority of homes were still circular dig-outs in the ground. The raised homes helped prevent spoilage from dampness and rodents. The increase in rice consumption also explains why the Yayoi were generally taller than the Jomon people.

The Yayoi people were also known for burying their dead in graves. Before burying them, the deceased would be placed in large ceramic urns or stone coffins. These graves are surrounded by raised mounds or stone circles and are found in clusters which suggests that the deceased were buried in cemeteries of sorts, as opposed to simply being buried in random locations.

|

The Yayoi were the first Japanese to exit the stone age and begin using metals. Iron was used to create utilitarian goods, such as farming implements, and construction materials, such as reinforcements to hold raised buildings. Bronze was used to build more luxurious items. One such item was called the dotaku, which was a long and narrow shaped bell.

|

|

Dotaku

Whereas the Yayoi people used iron and bronze, the geographical area of Japan has very limited metal resources. Most mines in Japan mine coal. Those people who settled near areas with iron and bronze became a bit richer than the rest. However, metals were not the only way to wealth. Many other luxuries were produced during this time such as silk and glass. Increased trading led to greater specialization in the workforce and thus greater wealth of the people. Asahi, located in today's Aichi Prefecture, is the largest Yayoi settlement and market found yet. It spans some 200 acres, whereas most settlements only spanned 5-70 acres.

With localized centers of power came attempts to control resources. This led to political agreements between 'chiefdoms' that led to small kingdoms. This, in turn, led to civil wars. The first recorded war in all of Japanese history took place during the Yayoi period. It was a civil war that took place sometime in the mid-to-late 2nd century. However, to call this war "recorded" is a bit of a stretch, as the "record" is merely a few footnotes at the end of various books written in China.

It is during the Yayoi period that we encounter the first written mention of Japan. Japan is first called "The Land of Wa" -- which literally meant "The Land of Dwarves" -- in the Han Shu (The History of the Han), written around the year 100 AD in China. The document mentions some 100 tribes, some of which sent envoys to pay tribute to the Chinese.

In a different document, the Wei Chih (History of Wei), written in 297 AD, describes the Land of Wa with a bit more detail. It describes Japan as a place with low crime levels, draconian punishment, polygamy, and superstition. In the Wei Chih, Japan is mentioned in the section labeled "the Eastern Barbarians", along with the people of Korea and Mongolia. Furthermore, the document informs us that a dominant kingdom exists: the Yamatai-koku (most likely the Yamato). Although the location of Yamatai is in dispute - many believe it is the same location as the Yamato in the Nara Basin area - they were ruled over by an unmarried shaman-queen named Himiko (See below) who came to power after a previous ruler of some 80 years passed.. It was the central area of power in Japan.

With localized centers of power came attempts to control resources. This led to political agreements between 'chiefdoms' that led to small kingdoms. This, in turn, led to civil wars. The first recorded war in all of Japanese history took place during the Yayoi period. It was a civil war that took place sometime in the mid-to-late 2nd century. However, to call this war "recorded" is a bit of a stretch, as the "record" is merely a few footnotes at the end of various books written in China.

It is during the Yayoi period that we encounter the first written mention of Japan. Japan is first called "The Land of Wa" -- which literally meant "The Land of Dwarves" -- in the Han Shu (The History of the Han), written around the year 100 AD in China. The document mentions some 100 tribes, some of which sent envoys to pay tribute to the Chinese.

In a different document, the Wei Chih (History of Wei), written in 297 AD, describes the Land of Wa with a bit more detail. It describes Japan as a place with low crime levels, draconian punishment, polygamy, and superstition. In the Wei Chih, Japan is mentioned in the section labeled "the Eastern Barbarians", along with the people of Korea and Mongolia. Furthermore, the document informs us that a dominant kingdom exists: the Yamatai-koku (most likely the Yamato). Although the location of Yamatai is in dispute - many believe it is the same location as the Yamato in the Nara Basin area - they were ruled over by an unmarried shaman-queen named Himiko (See below) who came to power after a previous ruler of some 80 years passed.. It was the central area of power in Japan.

Himiko

Himiko

Himiko (卑弥呼) is described as preoccupying herself with witchcraft and sorcery and bewitching people, and finally coming to power after years of warfare. It is said that she came to power by bewitching the other kingdoms.

As she ruled, she lived within a fortress and was guarded by 100 men. She almost never came out. She had a single male attendant, but was served on by some 1,000 women. Her male attendant was the means through which she communicated to the outside world. Her younger brother helped her with the task of ruling the land and she preoccupied herself with spiritual matters.

She had her regal status officially recognized by the Chinese in 238 AD when she had a tributary delegation sent to the Chinese emperor. However, unlike the many other kingdoms that partook in similar actions, she seems to have been recognized as the ruler of all the land of Wa. She even received gifts from the emperor: cloths, jewels, and mirrors. She was known to have given slaves, cloths, and cinnabar.

She died in 248 when she was 65. One hundred slaves were sacrificed with her death, and a king was placed on the throne. However, no one obeyed him, and chaos ensued throughout the land of Wa until a 13 year old relative of Himiko named Iyo came to the head of the land. She was buried in a large tomb, some 100 paces in diameter. Her tomb has likely been discovered in 2009 by a group of Japanese archaeologists. If the tomb truly is Himiko's, then it is the Hashihaka Kofun, located in modern-day Sakurai, in Nara Prefecture. To see the exact location, copy and paste the following into google maps: 日本奈良県桜井市箸中 倭迹迹日百襲姫大市墓.

In the Nihon Shoki, it is strange to find that Himiko's name is not mentioned even once, especially when one comes to realize that the document refers to the Wei Chih numerous times. She is briefly mentioned, but not by name, and the particulars of her reign are overlooked.

As she ruled, she lived within a fortress and was guarded by 100 men. She almost never came out. She had a single male attendant, but was served on by some 1,000 women. Her male attendant was the means through which she communicated to the outside world. Her younger brother helped her with the task of ruling the land and she preoccupied herself with spiritual matters.

She had her regal status officially recognized by the Chinese in 238 AD when she had a tributary delegation sent to the Chinese emperor. However, unlike the many other kingdoms that partook in similar actions, she seems to have been recognized as the ruler of all the land of Wa. She even received gifts from the emperor: cloths, jewels, and mirrors. She was known to have given slaves, cloths, and cinnabar.

She died in 248 when she was 65. One hundred slaves were sacrificed with her death, and a king was placed on the throne. However, no one obeyed him, and chaos ensued throughout the land of Wa until a 13 year old relative of Himiko named Iyo came to the head of the land. She was buried in a large tomb, some 100 paces in diameter. Her tomb has likely been discovered in 2009 by a group of Japanese archaeologists. If the tomb truly is Himiko's, then it is the Hashihaka Kofun, located in modern-day Sakurai, in Nara Prefecture. To see the exact location, copy and paste the following into google maps: 日本奈良県桜井市箸中 倭迹迹日百襲姫大市墓.

In the Nihon Shoki, it is strange to find that Himiko's name is not mentioned even once, especially when one comes to realize that the document refers to the Wei Chih numerous times. She is briefly mentioned, but not by name, and the particulars of her reign are overlooked.