Japanese Pirates!

Spelling may differs from source to source.

In Japan, the movie Pirates of the Carribean was a smashing success with countless Japanese women swooning over Jack Sparrow.

Well, move over Johnny Depp. Quite a few Japanese don't know this, but it turns out that pirating was quite the life style in Japan for well over a millennium. Japanese pirates, the Wakou (倭寇 - to be totally fair, this term originates from China and came to encompass all East-Asian pirates, not just Japanese. However, the term literally means Japanese Banditry), have a recorded history of attacking mainland Asia beginning as early as 414 AD. This earliest mention of "Japanese Pirates" - the literal translation of 倭寇 - comes from the Gwangaeto Stele, an historical rock with engravings upon it located in modern Korea.

The stele might not be the best source for factual history, however, because it seems to discuss quite a bit of mythology and folklore. That is, after discussing a story about dragons and people coming out of eggs, it begins to discuss the deeds of a "Great King Churyu", aka "King Yongnak". The Stele's quote regarding pirates states that "... the Wa had, since the sinmyo year (391), been coming across the sea to wreak devastation". "The Wa" are the Japanese. The stele then continues, describing that the Paekche entered into a peace treaty with the Japanese, and discusses how the Goguryeo kingdom drove the masses of Japanese people out of Korea. (See "The Yamato Period".)

Now, it may not be appropriate to call these individuals "pirates", as they seem to have been in Korea in a government sanctioned capacity. After all, if a pirate is approved by the government to rob and steal, are they a pirate, a privateer, or a member of the Navy?

Well, move over Johnny Depp. Quite a few Japanese don't know this, but it turns out that pirating was quite the life style in Japan for well over a millennium. Japanese pirates, the Wakou (倭寇 - to be totally fair, this term originates from China and came to encompass all East-Asian pirates, not just Japanese. However, the term literally means Japanese Banditry), have a recorded history of attacking mainland Asia beginning as early as 414 AD. This earliest mention of "Japanese Pirates" - the literal translation of 倭寇 - comes from the Gwangaeto Stele, an historical rock with engravings upon it located in modern Korea.

The stele might not be the best source for factual history, however, because it seems to discuss quite a bit of mythology and folklore. That is, after discussing a story about dragons and people coming out of eggs, it begins to discuss the deeds of a "Great King Churyu", aka "King Yongnak". The Stele's quote regarding pirates states that "... the Wa had, since the sinmyo year (391), been coming across the sea to wreak devastation". "The Wa" are the Japanese. The stele then continues, describing that the Paekche entered into a peace treaty with the Japanese, and discusses how the Goguryeo kingdom drove the masses of Japanese people out of Korea. (See "The Yamato Period".)

Now, it may not be appropriate to call these individuals "pirates", as they seem to have been in Korea in a government sanctioned capacity. After all, if a pirate is approved by the government to rob and steal, are they a pirate, a privateer, or a member of the Navy?

|

Now, it may not be appropriate to call these individuals "pirates", as they seem to have been in Korea in a government sanctioned capacity. After all, if a pirate is approved by the government to rob and steal, are they a pirate, a privateer, or a member of the Navy?

|

|

"Real" Piracy

Before we continue, let's make sure that we're not confusing "pirates" with "completely unorganized ruffians". Many of the Japanese pirates were known to exhibit strategies similar to those of the Samurai of the time. Perhaps some samurai resorted to the life of piracy?

Either way, the first recorded "real" act of piracy in Japan took place in the summer of 1223, on the coast of southern Goryeo Korea (spelling of places varies from source to source) ; the target was Gumju, according to the Goryeosa.

Following this act, many more recorded attacks took place. It appears that the growing number of attacks began to annoy those in command in the Korean Peninsula, as the leaders put pressure on the Kamakura shogunate to take care of the situation. To help placate the Korean leadership, the shogunate's commissioner in Kyuushyuu, Mutou Sukeyori, beheaded some 90 suspected pirates in front of a Korean envoy in the year 1227.

However, piracy continued. In 1263, more pirates raided Korean cities and locales. Between 1376 and 1385, at least 174 recorded Japanese raids of Korea took place. The raids became more and more daring, and the pirates went further and further inland, even as far in as modern day Pyongyang. Much of the booty seized were grains and people for slavery and/or ransom. It is believed that this dramatic piracy helped lead to the downfall of the Goryeo Dynasty in 1392. Those who could successfully defend against the 倭寇 became famous: the founder of the Joseon Dynasty, Yi Seonggye, came to predominance due to his success in repelling the 倭寇.

Many of these pirates came from Kyuushyuu and Tsushima. At the time, neither was under direct control by the Muromachi shogunate, the leading power center in Japan at the time. Kyuushyuu was under the sway of the Southern Court, which was developed by Emperor Go-Daigo. It was created when Ashikaga Takauji captured Kyoto in 1336, forcing the Emperor to flee to Yoshino, in the south of Kyoto. The Southern Court lasted for some 50 years battling the Northern Court. The Northern Court held the power of the Muromachi shogunate, founded by Ashikaga. Thus, promises by the Muromachi shogunate to help tide in the pirates were largely empty. In 1381 the shogunate prohibited such "outlaws" (悪党, あくとう), to little effect. However, some good came of the attempts: some 100 prisoners taken by the 倭寇 were returned to the Goryeo government.

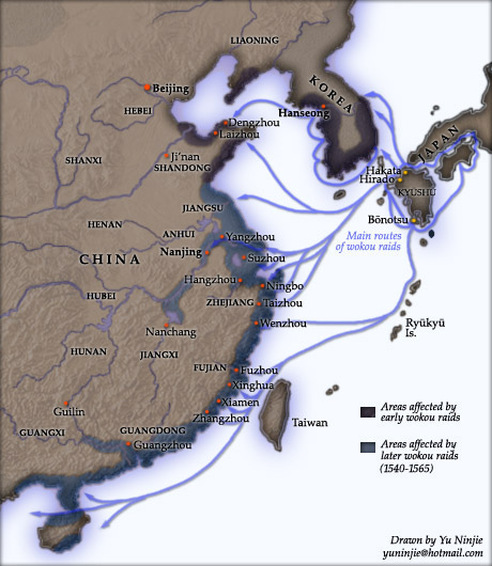

The 倭寇 didn't only attack Korea, however. As is shown in the map above, a popular target was also the Chinese territories near Korea. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties (Chinese), China had placed a trade embargo on Japan. This made Chinese goods hard to come by and, thus, valuable. The logical response? PIRACY! Throughout the 1300s, numerous successful raids by Japanese pirates took place. The raids became so bad that the Emperor of China demanded forts along the Eastern coast (the remains of which can still be seen today), and sent an envoy to talk with the Japanese government (specifically Prince Kanenaga, a member of the Southern Court). In 1369, the envoy threatened invasion if the attacks didn't end...

... so the Prince had the envoy killed. YAR HAR HAR!! However, in 1370, another envoy was sent, and he succumbed. The year after, more than 70 people were returned to China.

The good ol' days of pirating wouldn't last forever, however. In 1389 and 1419, Koreans attacked the pirate bases on Tsushima. Tsushima had long been considered, by Korea, as Korean territory under occupation by the Japanese, and this was seen by Korea as their liberating an occupied land. In 1389, the attacks led to hundreds killed, some 300 ships burnt, and hundreds of the pirate's victims saved. The 1419 attacks were known as the Ooei Invasion. However, a Japanese army helped the pirates fight off the attack, and eventually a truce was reached. The result was that trade would be opened up between the countries (a Korean concession), and that the Japanese would work harder to fight the pirates.

Either way, the first recorded "real" act of piracy in Japan took place in the summer of 1223, on the coast of southern Goryeo Korea (spelling of places varies from source to source) ; the target was Gumju, according to the Goryeosa.

Following this act, many more recorded attacks took place. It appears that the growing number of attacks began to annoy those in command in the Korean Peninsula, as the leaders put pressure on the Kamakura shogunate to take care of the situation. To help placate the Korean leadership, the shogunate's commissioner in Kyuushyuu, Mutou Sukeyori, beheaded some 90 suspected pirates in front of a Korean envoy in the year 1227.

However, piracy continued. In 1263, more pirates raided Korean cities and locales. Between 1376 and 1385, at least 174 recorded Japanese raids of Korea took place. The raids became more and more daring, and the pirates went further and further inland, even as far in as modern day Pyongyang. Much of the booty seized were grains and people for slavery and/or ransom. It is believed that this dramatic piracy helped lead to the downfall of the Goryeo Dynasty in 1392. Those who could successfully defend against the 倭寇 became famous: the founder of the Joseon Dynasty, Yi Seonggye, came to predominance due to his success in repelling the 倭寇.

Many of these pirates came from Kyuushyuu and Tsushima. At the time, neither was under direct control by the Muromachi shogunate, the leading power center in Japan at the time. Kyuushyuu was under the sway of the Southern Court, which was developed by Emperor Go-Daigo. It was created when Ashikaga Takauji captured Kyoto in 1336, forcing the Emperor to flee to Yoshino, in the south of Kyoto. The Southern Court lasted for some 50 years battling the Northern Court. The Northern Court held the power of the Muromachi shogunate, founded by Ashikaga. Thus, promises by the Muromachi shogunate to help tide in the pirates were largely empty. In 1381 the shogunate prohibited such "outlaws" (悪党, あくとう), to little effect. However, some good came of the attempts: some 100 prisoners taken by the 倭寇 were returned to the Goryeo government.

The 倭寇 didn't only attack Korea, however. As is shown in the map above, a popular target was also the Chinese territories near Korea. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties (Chinese), China had placed a trade embargo on Japan. This made Chinese goods hard to come by and, thus, valuable. The logical response? PIRACY! Throughout the 1300s, numerous successful raids by Japanese pirates took place. The raids became so bad that the Emperor of China demanded forts along the Eastern coast (the remains of which can still be seen today), and sent an envoy to talk with the Japanese government (specifically Prince Kanenaga, a member of the Southern Court). In 1369, the envoy threatened invasion if the attacks didn't end...

... so the Prince had the envoy killed. YAR HAR HAR!! However, in 1370, another envoy was sent, and he succumbed. The year after, more than 70 people were returned to China.

The good ol' days of pirating wouldn't last forever, however. In 1389 and 1419, Koreans attacked the pirate bases on Tsushima. Tsushima had long been considered, by Korea, as Korean territory under occupation by the Japanese, and this was seen by Korea as their liberating an occupied land. In 1389, the attacks led to hundreds killed, some 300 ships burnt, and hundreds of the pirate's victims saved. The 1419 attacks were known as the Ooei Invasion. However, a Japanese army helped the pirates fight off the attack, and eventually a truce was reached. The result was that trade would be opened up between the countries (a Korean concession), and that the Japanese would work harder to fight the pirates.

The New Era of 倭寇: Not just for the Japanese anymore!

The raids died down for about a century. However, with increased trade restrictions imposed by China, and with island-wide war in Japan (the Sengoku Jidai), piracy increased. This newer era of pirates weren't "as Japanese" as they had been in the 13th and 14th centuries: the raiding parties consisted of Koreans, Chinese, Japanese, and even Portuguese. Just how Japanese were the new pirates? The experts are out on this question, but their claims run from "less than 10%" to "probably upwards of 90%". Either way, the pirates weren't only Japanese.

Also, interestingly, Japanese textbooks focus on this newer age of piracy, as opposed to both eras...

Most notable of all, a Chinese trader named Wang Zhi rebelled against tighter trade restrictions and launched a huge piracy expedition. Many items that could be purchased in China could have been sold in Japan for upwards of a 1,000% profit. However, trade restrictions from China increased, making such activity illegal. Attracted by the prospect of riches, many Japanese joined with Wang Zhi , and together they created great havoc. Matsuura Takanobu, a samurai of the Matsuura clan, became an ally of the Chinese pirate leader, Wang Zhi, in 1543. He invited the pirate leader to live and make his base in Hirado (an area very far west in Kyuushyuu). Through this strong friendship and aid, Wang Zhi was able to launch countless raids against China, and smuggle unbelievable wealth between borders. The piracy only subsided when China loosened trade restrictions, and when the Regent of Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, launched a massive campaign in 1588 to disarm the Japanese public.

In 1585, a Japanese pirate by the name of Shirahama Kenki conducted pirate raids among the coastal areas of Vietnam. His five ships, however, were driven away (two destroyed) by a fleet of at least 10 Vietnamese ships. Apparently due to a mistaken identity, Shirahama was allowed to escape. Fifteen years later, his ship crashed and he was taken prisoner by the Vietnamese. His capture was used as a reason - "how shall we go about to effectively stop Japanese pirates?" - to begin opening friendly talks with the newly "appointed" shogun of Japan, Tokugawa Ieyasu.

There seem to have been other "pirates" of the time, however I'm not including them here due to their "lack-of-pirateness". Indeed, many of these supposed pirates just seem to be considered pirates because they attacked people using raids by boats. However, the targets were political enemies, as opposed to 'anyone with stealable loot', and the purposes were militaristic in nature, as opposed to trying to get rich off of plunder. Thus, it would seem much more reasonable to call these individuals something along the lines of 'Generals of clan navies', or privateers. Fuuma Kotarou falls under this category.

Also, interestingly, Japanese textbooks focus on this newer age of piracy, as opposed to both eras...

Most notable of all, a Chinese trader named Wang Zhi rebelled against tighter trade restrictions and launched a huge piracy expedition. Many items that could be purchased in China could have been sold in Japan for upwards of a 1,000% profit. However, trade restrictions from China increased, making such activity illegal. Attracted by the prospect of riches, many Japanese joined with Wang Zhi , and together they created great havoc. Matsuura Takanobu, a samurai of the Matsuura clan, became an ally of the Chinese pirate leader, Wang Zhi, in 1543. He invited the pirate leader to live and make his base in Hirado (an area very far west in Kyuushyuu). Through this strong friendship and aid, Wang Zhi was able to launch countless raids against China, and smuggle unbelievable wealth between borders. The piracy only subsided when China loosened trade restrictions, and when the Regent of Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, launched a massive campaign in 1588 to disarm the Japanese public.

In 1585, a Japanese pirate by the name of Shirahama Kenki conducted pirate raids among the coastal areas of Vietnam. His five ships, however, were driven away (two destroyed) by a fleet of at least 10 Vietnamese ships. Apparently due to a mistaken identity, Shirahama was allowed to escape. Fifteen years later, his ship crashed and he was taken prisoner by the Vietnamese. His capture was used as a reason - "how shall we go about to effectively stop Japanese pirates?" - to begin opening friendly talks with the newly "appointed" shogun of Japan, Tokugawa Ieyasu.

There seem to have been other "pirates" of the time, however I'm not including them here due to their "lack-of-pirateness". Indeed, many of these supposed pirates just seem to be considered pirates because they attacked people using raids by boats. However, the targets were political enemies, as opposed to 'anyone with stealable loot', and the purposes were militaristic in nature, as opposed to trying to get rich off of plunder. Thus, it would seem much more reasonable to call these individuals something along the lines of 'Generals of clan navies', or privateers. Fuuma Kotarou falls under this category.

Everybody was Kung Fu Fighting

This new era of piracy got to be such a major issue that the Chinese government had to resort to some rather unusual tactics: the ever-so-famous Shaolin Monks were even called on to fight the 倭寇 pirates. For those unfamiliar, the Shaolin Monks were/are monks named from the Chinese Shaolin Temple, which has existed for well over 1500 years, who were known for their specialized form of kung fu.

Due to a bit of ineffectiveness on the part of the Chinese Imperial army and navy, a commander named Wan Biao asked the monks to help fight the piracy. The epic and long-awaited war to decide which is cooler - pirates or kung fu masters (sorry, no ninjas) - took place in 1553 in at least four battles. The first battle took place in spring, on Mount Zhe, near Hangzhou City. The monks were triumphant. The second battle - the Battle of Wengjiangang - was fought in the Huangpu River Delta on July 21st. The monks slaughtered everyone - women, too - over a 10 day battle, and suffered only four casualties. There were at least two more battles, and the fourth battle was a tragic loss for the monks. The defeat was apparently due to poor tactics, and encouraged the monks to stop helping the Emperor.

Due to a bit of ineffectiveness on the part of the Chinese Imperial army and navy, a commander named Wan Biao asked the monks to help fight the piracy. The epic and long-awaited war to decide which is cooler - pirates or kung fu masters (sorry, no ninjas) - took place in 1553 in at least four battles. The first battle took place in spring, on Mount Zhe, near Hangzhou City. The monks were triumphant. The second battle - the Battle of Wengjiangang - was fought in the Huangpu River Delta on July 21st. The monks slaughtered everyone - women, too - over a 10 day battle, and suffered only four casualties. There were at least two more battles, and the fourth battle was a tragic loss for the monks. The defeat was apparently due to poor tactics, and encouraged the monks to stop helping the Emperor.

Bibliography for this page

|

Here is a fantastic book that I found after writing all this that talks in depth about Japanese piracy. I'm going to add some information from it to this sight soon. (4/4/13)

I highly recommend this book for those who want to learn about Japanese piracy! Unfortunately, most Japanese history textbooks written in English largely glance over the 倭寇, and thus the vast majority of information is only available online. Here are the sites I used. Even then, most websites on the subject were just reposts of the Wikipedia entry. Other sites referenced books that were nothing more than printed copies of the Wikipedia entry -- no joke: they were actually books that were just Wikipedia copy and pasted.

I tried to make this site as much an amalgamation of sources as possible, and I'm working on translating Japanese sources. |

|

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wokou

http://www.hunaneagle.com/blog/passivism-and-radicalism-ii/#comment-2

http://asianhistory.about.com/od/warsinasia/a/shaolinvpirates.htm

Here's a professor working on the subject. I'm attempting to communicate with him to gain a better understanding of the subject.

Associate Professor Peter Shapinsky of the University of Illinois Springfield

http://www.hunaneagle.com/blog/passivism-and-radicalism-ii/#comment-2

http://asianhistory.about.com/od/warsinasia/a/shaolinvpirates.htm

Here's a professor working on the subject. I'm attempting to communicate with him to gain a better understanding of the subject.

Associate Professor Peter Shapinsky of the University of Illinois Springfield